Native American Heritage in Sonoma County

November is Native American Heritage Month, but you can celebrate Native American heritage all year long in Sonoma County. Long before we became known as Wine Country, Sonoma County was home to thousands of Native Americans, including those of the Pomo, Miwok, and Wappo tribes. And despite mass displacement, humiliation, illness, and death at the hands of European and American colonists, Native American cultures and presence persist in modern-day Sonoma County.

Connecting to the Land

One of the most significant Native American sites in the county is Tolay Lake, which many Northern California tribes believed to have healing powers. Set eight miles south of Petaluma, the lake is now part of 3,402-acre Tolay Lake Regional Park, where more than 11 miles of trails cross extensive grasslands and open ridges with views of San Pablo Bay, the San Francisco skyline, and Bay Area peaks.

Petaluma was part of the sprawling ancestral lands of the Coast Miwok tribe, who collectively called the area Peta Lumaa. Their territory stretched throughout the southern reaches of the county between Petaluma, Valley Ford and the city of Sonoma, and west to the Pacific Ocean and Bodega Bay.

Enroute to Bodega Bay, the hamlet of Occidental is home to the 80-acre Occidental Arts & Ecology Center, which champions the balanced, restorative methods of agriculture employed by the Coast Miwok and other area Native people for centuries.

The rugged, wild, and stunning landscape of Bodega Bay is now protected within Sonoma Coast State Park. Here you’ll find the tiny cove of Miwok Beach and the wide sands of lagoon-studded Salmon Creek Beach; the latter is popular for surfing and bonfires, and formerly home to the Coast Miwok settlement of Pulya-lakum.

Central Wappo lived at the northern end of the Russian River Valley, around northern Santa Rosa and Healdsburg. Their ancestral homelands included the 3,200-acre Pepperwood Preserve, an ideal place to connect with the natural beauty, wildlife, and serenity of Sonoma County.

Kashia Pomo territory encompassed much of the county’s central coast, from roughly the village of Bodega to Stewart’s Point, including Fort Ross—where just nearby, they had an important seasonal settlement of their own, Metini.

Southern Pomo territory encompassed almost the entirety of what is now the Highway 101 corridor. From Cotati and Rohnert Park, Southern Pomos lived throughout Santa Rosa, into Healdsburg and Cloverdale in the north, and west to what is now the Lake Sonoma Recreation Area.

In the northern reaches of the county, the Western Wappo lived in what is now Alexander Valley wine country. Their territory stretched from Lytton Springs to the Geyserville area, where two settlements had special significance to the name “Sonoma County”: Tsi’mitu-tso-noma, on the east bank of the Russian River, and near the Geysers, Tekanan-tso-noma.

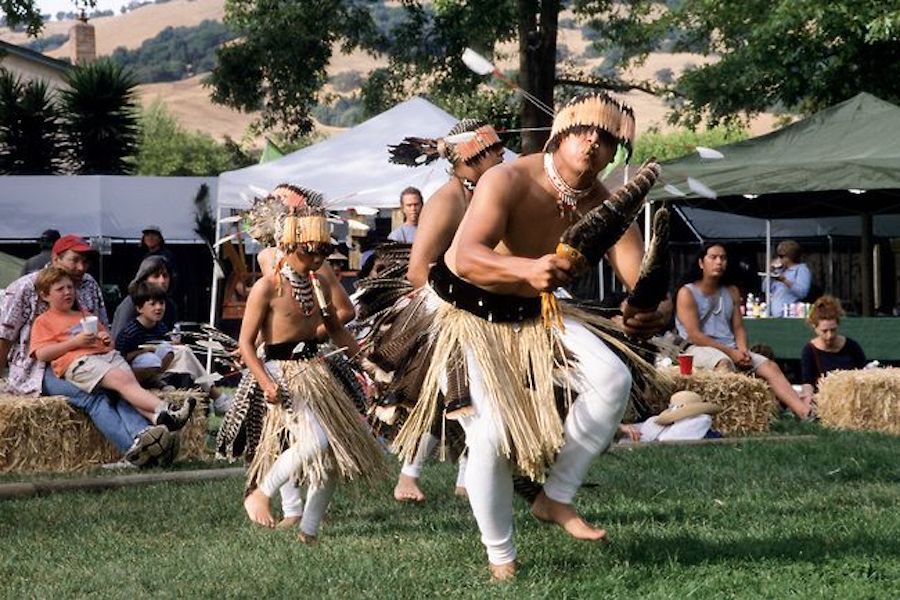

Ancestors of all these tribes still live in Sonoma County, belonging to tribal groups such as the Cloverdale Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians of the Stewarts Point Rancheria, the Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians, and the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria.

Celebrating Native Arts & Culture

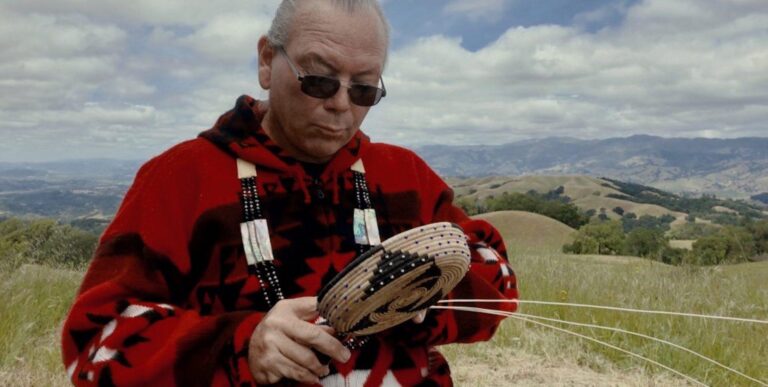

On the Santa Rosa Junior College campus, the SRJC Multicultural Museum is home to more than 5,000 cataloged items, and traditional Native American art makes up the greatest portion of the collection. All of North America’s Indian tribes are represented, and art forms include ceramics, basketry, beadwork, sculpture, textiles, and jewelry.

Also in Santa Rosa, the California Indian Museum and Cultural Center (CIMCC) portrays California history and culture from a uniquely Native American perspective. The museum’s varied exhibits represent California’s Indian culture statewide, which includes more than 150 tribes.

Shopping for Native Creations

The CIMCC’s museum store is run by participants in the Center’s Native Youth Employment Training program, and features the creations of Native artists working in abalone, basketry, and other native materials. Many of these artists hail from Sonoma County, such as Cloverdale brothers Matthew & Michael Molina of apparel brand Lucid Luck.

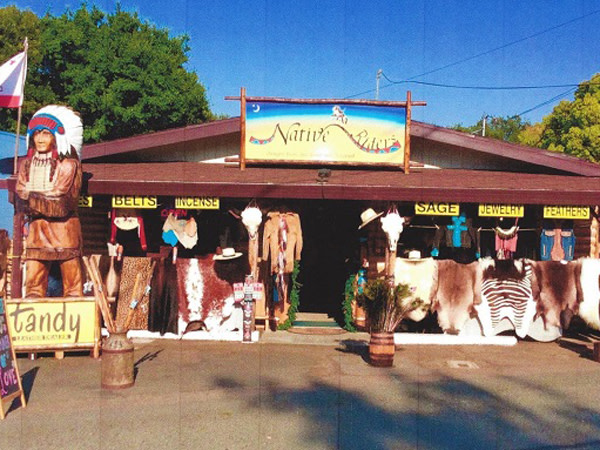

Sebastopol-based craftsman Kerry Mitchell (aka Lone Eagle), whose family heritage is Comanche, adds embellishments like beads, feathers, or coins to his leather works, and also creates exquisite wearable pieces from denim and vintage wool. He sells his work at his funky Sebastopol shop, Native Riders, as well as various works by craftspeople from 26 other tribes.

Making a Bet on the Future

In 1958, the U.S. Congress stripped California’s 41 rancherias—a name for Native-reserved land that dates to Mexico’s political presence in California—of federal status, making them in-eligible for funding and services from the government. After a long struggle, the California rancherias’ federal status was returned to them in 2000 by President Clinton.

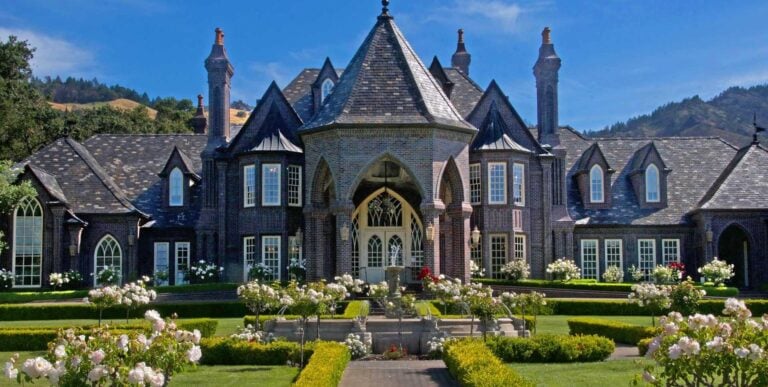

In 2005, the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, which includes both Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo, were able to purchase land in Rohnert Park, proposing to build a gaming facility there. After a long process of approval, the Graton Resort & Casino was opened in 2013.

In addition to 200 guestrooms, a spa, and a pool, Graton Resort & Casino features a wide variety of slots and table games, including Blackjack, Baccarat, and poker. Even if you’re not into gambling, though, stellar restaurant options make this a popular destination for a big night out.

Since 2002, the Dry Creek Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians has operated its own gaming facility, Geyserville’s River Rock Casino. Featuring roughly 1,000 slot machines, 18 table games, smoke-free gaming, and three eateries, the casino is surrounded by Alexander Valley vineyards. This gorgeous view can be enjoyed at leisure from the casino’s Valley Deck.

The Enduring Legacy of Fry Bread

Quite possibly the most unassuming eatery in Sonoma County, the Fry Bread Shop inhabits a small counter inside a Santa Rosa convenience store, turning dough made from traditional Blue Bird Flour (milled on the Navajo Nation reservation in Colorado) into fry bread tacos, pizzas, and even desserts.

Across the western United States, crispy-chewy fry bread is considered a Native American staple. This simple delicacy might never have existed, though, if the U.S. government hadn’t displaced Navajos from their Southwestern lands and marched them 300 miles away to Colorado internment camps. Here, starving Navajos were given government-issued rations of flour, salt, and lard, which they used to create fry bread—and thus survive. Today fry bread is eaten in a spirit of celebration, everywhere from home kitchens to ceremonial events like powwows.

Fry Bread owner Derek Muro is a graduate of the California Indian Manpower Consortium (CIMC), which via education and training enables Native Californians to meet their employment goals. The local popularity of his messy, delicious fry bread concoctions are proof of his success—but rather than take our word for it, we suggest you go try it for yourself. (Fry Bread Shop, 521 West 9th Street, Santa Rosa)

Native California Reading List

If you’d like to learn more about Sonoma County’s history in a Native context or from a Native perspective, check out one or more of these comprehensive books:

- Handbook of the Indians of California

- California Indians and Their Environment: An Introduction

- Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources

- We Are the Land: A History of Native California

Written by Melanie Wynne

Places Mentioned

THIS IS WINE COUNTRY.

Share your experience using #SonomaCounty or #LifeOpensUp